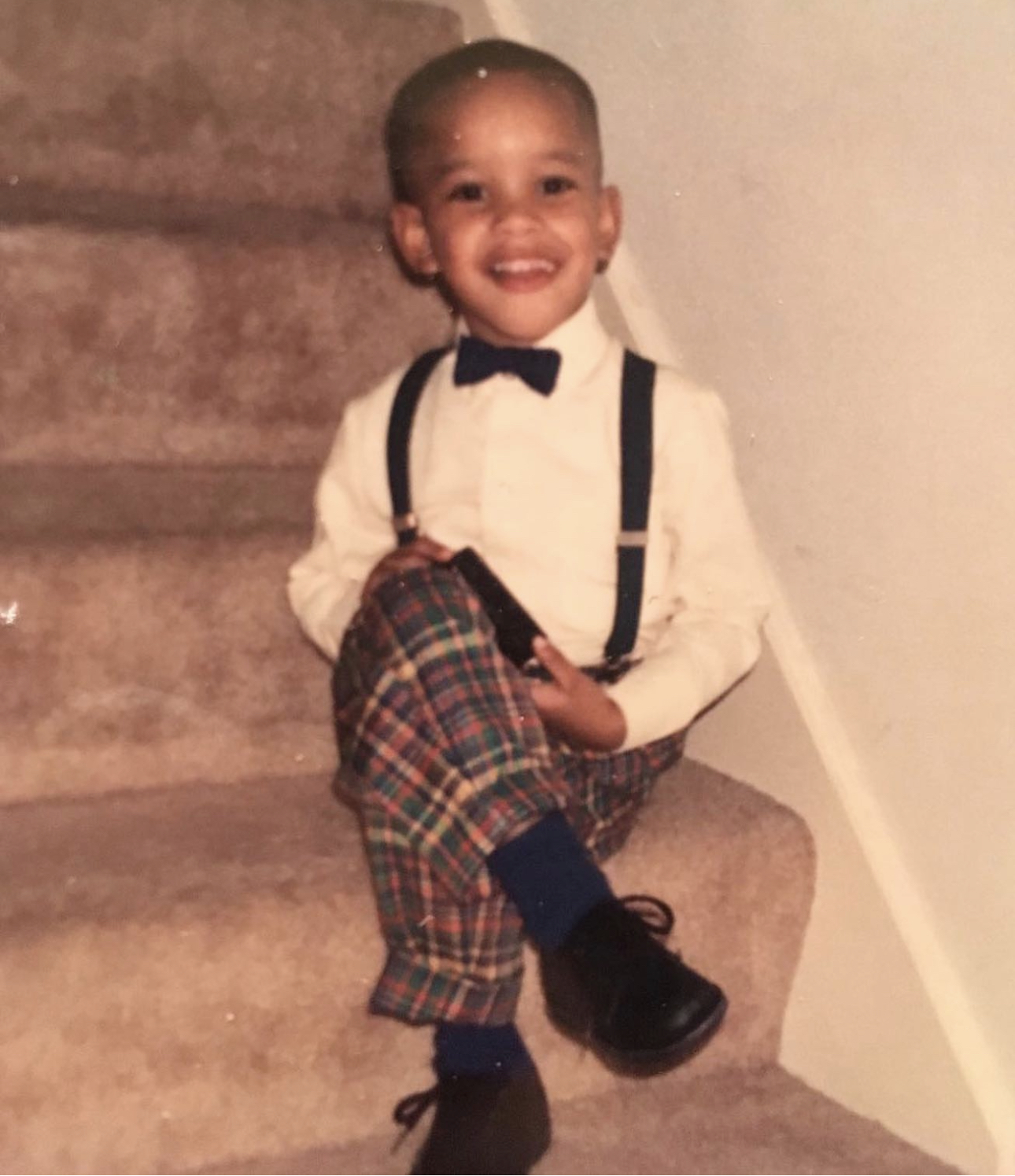

It was a hot, summer Houston day in 1994. Outside, the buzzing of cicadas could be heard under the swelling sun. Cameron J. Ross (Theatre ‘06) was seven years old. He was going to the local movie theater on I-10 East and Federal Road with his mother, where the matinees were one dollar. They were going to see Crooklyn, Spike Lee’s new coming-of-age film about a young Black girl named Troy and her life in 1970s Brooklyn. It was important to his mother that he be exposed to media that celebrated Black culture. At home, they watched shows like A Different World and The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air together as a family, with his father and his younger brother.

Little Cameron was excited to watch Crooklyn. He sat in the red cushioned movie theater seat with his favorite snack in hand: a tub of popcorn with a packet of M&Ms poured and mixed in. As the theater lights dimmed and the opening scenes began to play, Cameron was transfixed. The little kids playing hopscotch and double dutch in Brooklyn’s neighborhood of Bed-Stuy were fascinating to him. He played those games with his friends too, but his playground in Houston was lined with green suburban lawns and tall streetlights. For Troy, the nine-year-old character in Crooklyn, the entire city of New York was her playground — and its streets, lined with bodegas and drag queens and loud neighbors. Her independence awakened something within him.

Cameron didn’t know it then, but Crooklyn would have a big impact on him. For the first time, he could see a world outside of Houston, Texas. A world beyond the streetlights of his playground. He thought perhaps he would become a preacher or a doctor. But now, he could dream even bigger.

Cameron J. Ross is a multi-hyphenate: a TV writer, actor, and producer based in Hollywood — a dream that he has been working toward for the better part of a decade. He says the mission of his career is to express the full breadth of the Black experience in vivid imagery. In keeping with that mission, he won a Special Tony Award in 2021 for his work with an organization he founded called the Broadway Advocacy Coalition. The group’s goal is to ensure that the Broadway community plays a more impactful role in dismantling systemic racism. They were recognized by the Tony’s for their work which included a high-profile multi-day forum on race called “#BwayforBLM.” The forum examined how white supremacy has permeated the industry and how to approach racial equity. It was part of the national conversation around anti-Blackness in America following the murder of George Floyd in 2020.

Ross has written for the shows, The Summer I Turned Pretty and Gentefied on Amazon Prime and Netflix, respectively. He also previously acted on Lena Waithe’s BET comedy series, Boomerang. Now, he’s developing a new series (taking place in Houston) with a major studio. If his new show is greenlit, he will become part of a small group of Black showrunners that comprise 5% of all showrunners in Hollywood.

For Ross, getting to this point in his career as a credited creator, writer, and executive producer has been a storied journey of surrendering to his imagination.

—–

Sheron Ross, Cameron’s mother, was an actress, dancer, and the magnet coordinator for the arts program at Kashmere High School. She also coached Cameron’s performances. “She was my mom-ager,” Ross said. He remembers performing in his third grade talent show, singing “Sumthin’ Sumthin” by Maxwell. His mother choreographed the mid-song dance break: several 8-count movements of the eight year old doing “the bounce” and “raising the roof.” On stage, he felt free. The feeling of captivating his audience felt like volts of electricity pulsing through his young body.

But outside of performing, he was a careful child — fearful of expressing his creativity. Although he didn’t know he was gay yet, he was still teased for it. From an early age, he was keenly aware that his softness and vulnerability conflicted with the image of masculinity he knew. “I always felt that Black masculine culture never had space for me,” Ross said. “For survival, I stopped performing during middle school and decided to play sports.” During this time period, he bonded more with his father, who would drive him to football games and provide feedback on his plays. In the eighth grade, his mother asked if he wanted to audition for HSPVA’s theatre program, but Ross insisted that he wanted to play football at Northshore High School, his zoned school. His mother obliged.

One day, he saw a flier in the hallway to audition for the play, Boys Next Door by Tom Griffin. Ross was cast as the schizophrenic golf player, Barry. For the first time in years, that freeing feeling of being on stage rushed back to him, and he felt alive. He immediately asked his mother if it was too late to audition for HSPVA. Even though he was already into his freshman year, his mother managed to organize an audition, and he got a call back. “They felt like celebrities to me,” Ross said.

“I remember seeing Black boys that seemed so free and confident in who they were, the way they spoke and celebrated themselves.”

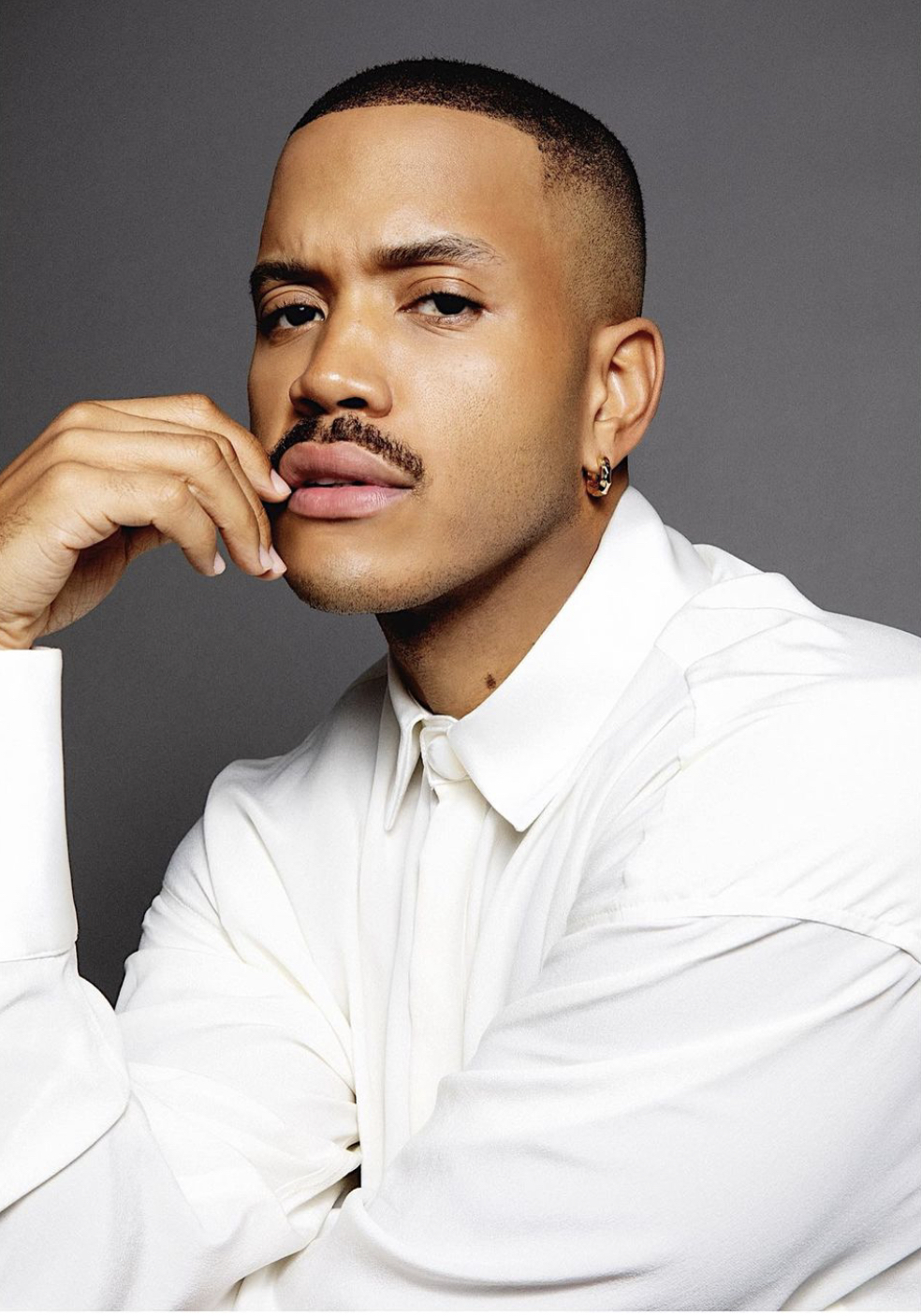

At the 74th Annual Tony Awards.

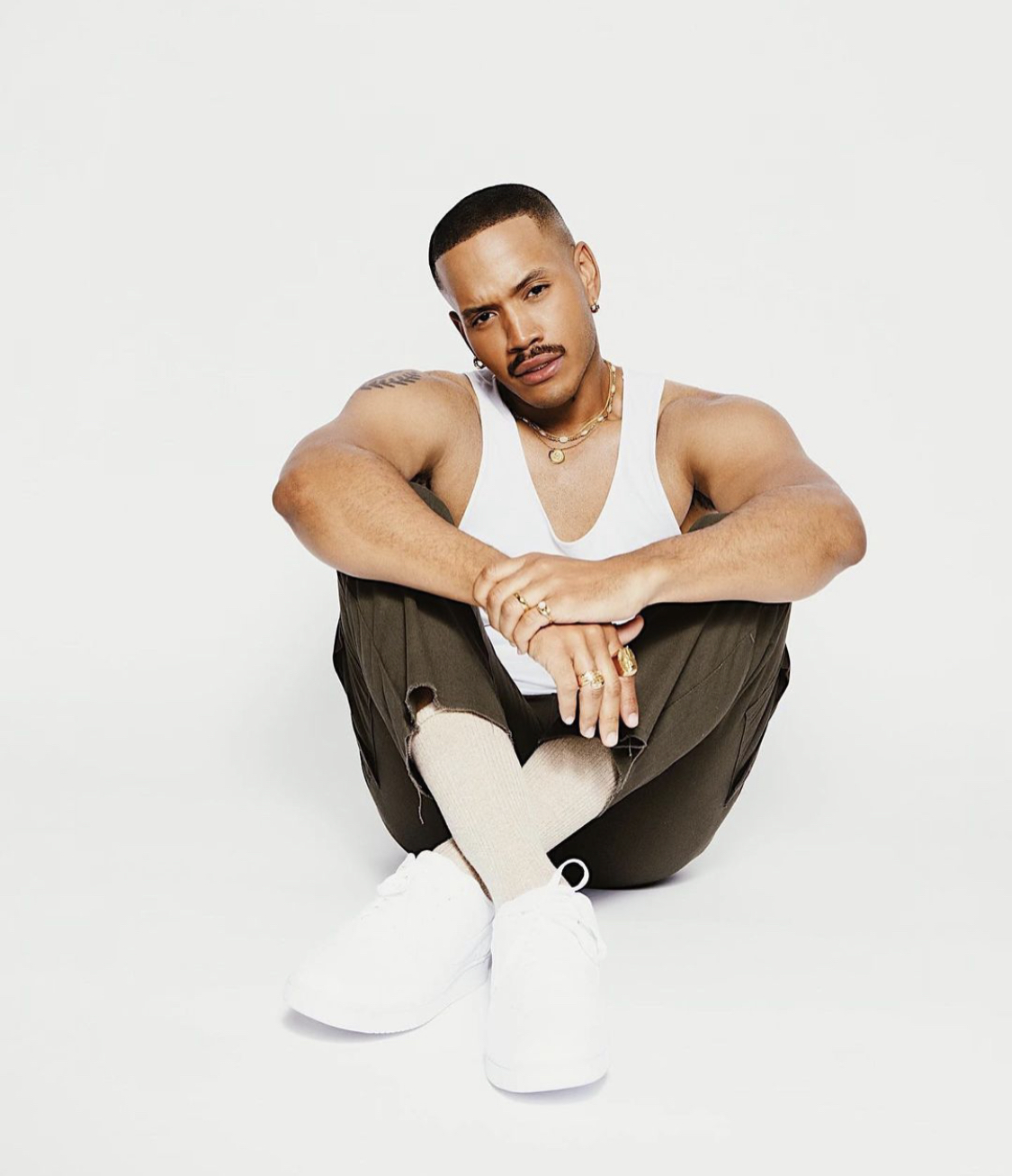

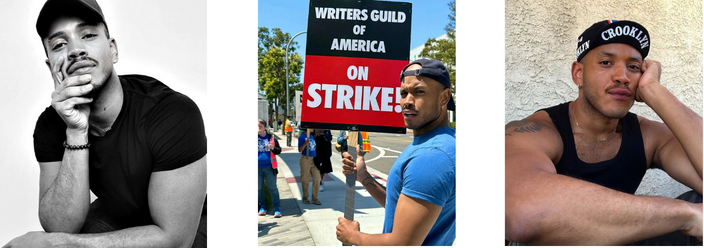

Playing the role of Dre in Lena Waithe’s Boomerang series on BET.

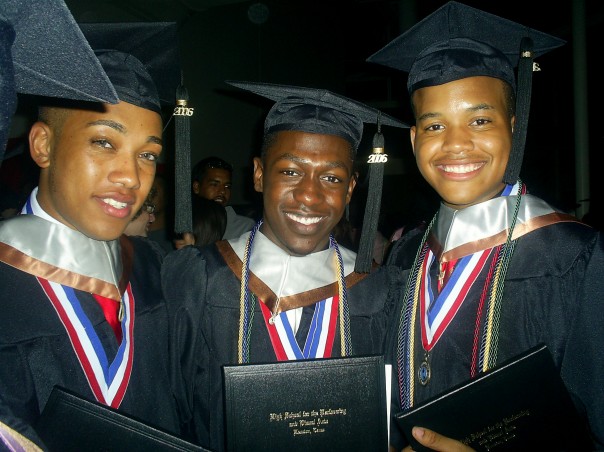

As a young boy in Houston, TX.

He got in. And the years that followed would change him. He would go on to meet classmates that would impact his career over a decade later.

Just like when he watched Crooklyn, HSPVA symbolized the life that was more than what he grew up knowing. He was exposed to new fashion and food and art. This caused tension between him and his father. He had become obsessed with Niko Niko’s, the Greek restaurant that was five minutes away from HSPVA’s 4001 campus. It was a staple for many students who wanted tasty food after rehearsal or before a show. “Mom, can we have Greek food tonight?” Ross asked. His mother was a great cook, and usually made Creole food for dinner. “Why do you want to eat that?” chimed in Ross’s father. He wanted his wife’s mac & cheese with ham hock or Crock-Pot beef stew every night for dinner. He struggled to understand why his son didn’t want that too. This friction became a dynamic in their relationship. One day, Ross convinced his father to try Niko Niko’s. “He didn’t say much when he tasted it. I knew he preferred my mom’s red beans and rice, but he still tried it because it was important to me,” Ross said. Ross’s father came to respect that his son was becoming enriched with new cultures and new outlooks on life. Even though he was changing, he supported him. It was at HSPVA where Ross was also first introduced to musical theatre, which he immediately fell in love with. He played the lead in the Theater Department’s 2006 production of Once on This Island. Chasing his dream of moving to New York, he majored in musical theater at the American Musical and Dramatic Academy (AMDA). His first New York bucket list item was to buy rush (discounted) tickets for The Color Purple on Broadway. He lined up by himself at 6am for the tickets that ended up being front row. It was one of the few productions on Broadway at the time that had an all-Black cast. It was a show where he could see himself playing a role, the role of Harpo. In fact, Ross even thought the actor playing Harpo that day, Brandon Victor Dixon, looked just like him. By age 23, Ross would go on to play the role of Harpo in the national tour of Oprah Winfrey Presents The Color Purple. He remembered trying on his costume shoes for the first time. When he looked down at the inner sole of the boot, “Brandon Victor Dixon” was written in Sharpie.

After two exciting years touring with The Color Purple, Ross began auditioning for other roles, but they were never the perfect match. He longed for the kinds of rich, dynamic Black characters he saw on TV while growing up. His breaking point came when he got an audition for Law & Order. It was a big deal. “As a stage actor, once you gained a Law and Order credit, it was like you’re now a real TV actor, and I wanted that badge,” Ross said. The audition was for the role of “Thug 3.” He didn’t end up booking it, but there was a part of him that was relieved. “Auditioning for that role as a Black man was demoralizing,” Ross said. He was frustrated that many of the roles he was being offered were negative stereotypes of Black Americans. He thought of the impact that Black cinema and TV had on him as a child. He remembered the feeling he got when he watched Crooklyn. Seeing that film as a young Black boy, he realized he was entitled to explore the endless opportunities and sceneries of life. For there to be more inspiring Black characters and stories, he had to create them.

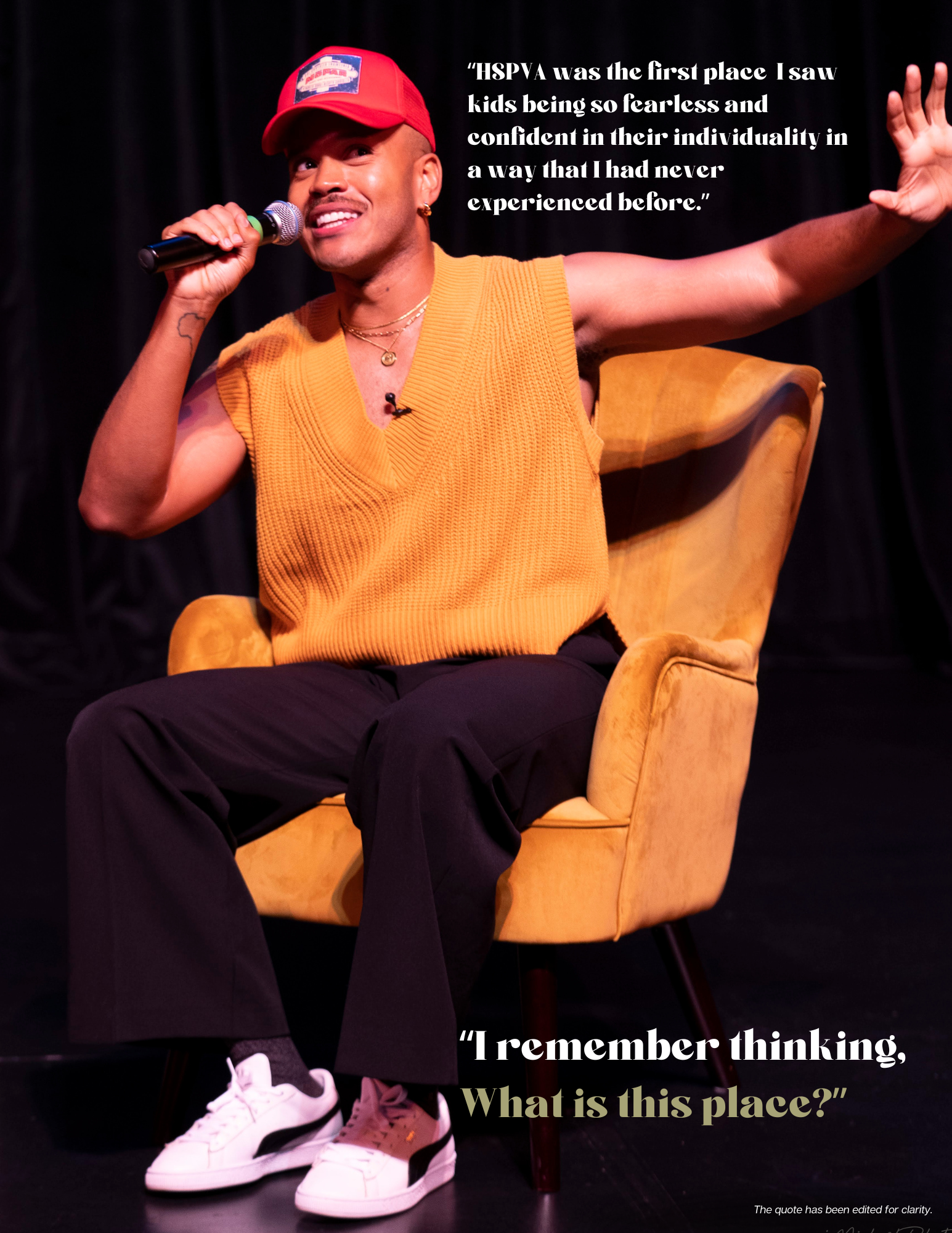

Speaking with Fox 2 Anchorwoman/Reporter Blair Ledet (Vocal ‘10) at HSPVA BAN’s “What I Wish I Knew LIVE: An Edutainment Series” at their 2022 Homecoming event.

In the national tour of Oprah Winfrey Presents: The Color Purple.

On the set of his short film, “They Come, They Go.”

“I wanted to make something that defied Black stereotypes, yet was still fresh and real,” Ross said. His first unofficial script was a revamp of A Different World called “Hillman,” named after the fictional HBCU that the original characters attended. Ross became so committed to becoming a writer that he left New York for Los Angeles.

“I only had $2,000 to my name, but I was going to make this happen,” Ross said.

He describes the next period of his life as the “struggle years.” Even though he was physically in LA, gaining entry into Hollywood writing rooms was a challenge. He didn’t know any TV executives, and he wasn’t a nepotism baby. To make ends meet, he took a marketing job at a beauty brand. Then, he worked as a production assistant at Viacom screening scripts from pitches. While the work wasn’t fulfilling, he was able to make valuable connections. He eventually decided that if he was going to be serious about his writing career, he needed to invest 100 percent of his effort into it. In 2019, he quit his job at Viacom and decided to put all of his energy into producing his very own short film titled “They Come, They Go.” He believed this would be his big break.

Low on cash and full of belief in himself, he moved out of his apartment and onto a friend’s couch in LA. That friend was Chaia Raibon (Theatre ‘06), one of Ross’s closest friends at HSPVA. During this time, most of his wardrobe found a home in the backseat of his 2008 Blue Honda Accord that he fondly named “Blue Ivy.” Officially homeless, he invested all $2,000 of his savings into his short film. To hire the production team, the cast, and the publicity team, he leveraged the connections he had made over the years. He invited everyone he knew to the Hollywood premiere.

A few hours before the premiere, Blue Ivy broke down. Sweating with anxiety, he propped open the hood, checked the battery, and troubleshooted the engine. After what felt like an hour, the car engine eventually started. Relieved, he pulled his “director’s outfit” from the backseat, quickly put it on, and sped over to make it in time.The film was so well received, Ross was signed as a writer and actor to The Gersh Agency, one of the top Hollywood agencies in America. He was floored. He had bet everything on himself, and it was finally paying off. He was going to become a Hollywood writer.

Since 2020, Ross has written and acted on major network shows, and his HSPVA network has continued to help him along the way. It was actually his PVA classmate, Dime Davis (Theatre ‘04), who encouraged him to read for the role of Dre in BET’s Boomerang. She was one of the showrunners and co-executive producers of the show, made by Lena Waithe’s production company, Hillman Grad Productions.

For the last year and a half, Ross has been busy developing a TV series with a major studio. In his own words, it’s “a love letter to Houston and to my mom.” The pressure he put on himself to deliver for his community mounted as Hollywood writers went on strike this year.

“It was scary because I wasn’t sure if all my hard work over the years was just going to fall through,” Ross said.

His show, along with all others, was stalled during the strike. Ross was nervous about his development deal getting canceled. The writer’s strike lasted nearly five months. It centered around the future role of streaming and artificial intelligence — and their effects on writers and their pay. Ross remembers the moment it ended. He happened to be in Houston. “I was on the couch, in the home I grew up in, constantly refreshing my email.” When he got the message that the deal reached was even better than expected, he breathed a sigh of relief.

With his classmates, Julius “Juju” Chase and Delius Doherty, at their HSPVA graduation in 2006.

A few hours before the premiere, Blue Ivy broke down. Sweating with anxiety, he propped open the hood, checked the battery, and troubleshooted the engine. After what felt like an hour, the car engine eventually started. Relieved, he pulled his “director’s outfit” from the backseat, quickly put it on, and sped over to make it in time.The film was so well received, Ross was signed as a writer and actor to The Gersh Agency, one of the top Hollywood agencies in America. He was floored. He had bet everything on himself, and it was finally paying off. He was going to become a Hollywood writer.

Since 2020, Ross has written and acted on major network shows, and his HSPVA network has continued to help him along the way. It was actually his PVA classmate, Dime Davis (Theatre ‘04), who encouraged him to read for the role of Dre in BET’s Boomerang. She was one of the showrunners and co-executive producers of the show, made by Lena Waithe’s production company, Hillman Grad Productions.

For the last year and a half, Ross has been busy developing a TV series with a major studio. In his own words, it’s “a love letter to Houston and to my mom.” The pressure he put on himself to deliver for his community mounted as Hollywood writers went on strike this year.

“It was scary because I wasn’t sure if all my hard work over the years was just going to fall through,” Ross said.

His show, along with all others, was stalled during the strike. Ross was nervous about his development deal getting canceled. The writer’s strike lasted nearly five months. It centered around the future role of streaming and artificial intelligence — and their effects on writers and their pay. Ross remembers the moment it ended. He happened to be in Houston. “I was on the couch, in the home I grew up in, constantly refreshing my email.” When he got the message that the deal reached was even better than expected, he breathed a sigh of relief.

Now the show is back in development, and Ross is ecstatic. It has taken years of hard work for him to reach this point in his career. He can’t help but thank his younger self, the same little Cameron who watched Crooklyn at the dollar matinee theater in 1994. He remembers the moment when that film gave him the permission to dream of a life bigger than what was expected of him.