“All the world’s a stage,” the famous quote begins, “and all the men and women merely players.” This opening phrase from Shakespeare’s As You Like It can suggest the idea that aspects of performance and performativity are interwoven throughout our day-to-day lives, both public and private. At any given moment, we are all actors in perpetual performance, often juggling multiple roles at once. Someone who appears to comfortably read books alone at the bar. Someone who “doesn’t need a straw” for their beverage. By observing and becoming aware of the seemingly subtle things we do (or don’t do) and say (or don’t say), what can we learn about the selves we portray and how we relate to one another? How do the people and the institutions around us affect our storylines? Engaging with the work of Autumn Knight (Theatre ‘98) has inspired me to deeply consider these questions.

Knight is a New York-based interdisciplinary artist working with performance, installation, video, and text. Some of her recent achievements include appearing in the 2019 Whitney Biennial, being chosen as a 2022-2023 Guggenheim Fellow in Creative Arts, and being tapped for Eldorado Ballroom, a music and film series co-curated by Solange and the Saint Heron Collective to honor the historic Black music hall in Houston’s Third Ward. In anticipation of her 2016-17 residency at The Studio Museum in Harlem, she offered this statement about her practice that seems to still hold relevance today: “My process builds on assessing the texture of relationships and exploiting/exposing the dirty absurdities and inaccuracies that lie in those bonds. Basically, where’s the lie?”

In her recurring performances of Sanity TV, a fictional talk show that “promotes neither sanity or insanity,” she masterfully navigates the discomfort zones around the lie. Playing the role of host, Knight assesses the texture of each group through careful observation. For several minutes, the cameras follow her as she does a walkabout, locking eyes with guests and occasionally repositioning them into new seats about the room. Microphones are placed for crowd interaction and screens project the home viewers’ perspective. The show begins to take form once everyone is settled, but the form it takes is almost entirely up to the live “in-studio” audience, specifically, the people Knight chooses to interview in front of the group. Her line of questioning is often so ridiculous, it almost feels like a Rorschach inkblot test. “So, your momma was a cat. What was that like growing up with your momma as a cat?” Somewhere in the audience member’s reply lies the answer to more intimate questions she didn’t explicitly ask. Somewhere in the room, someone is distracted by thoughts of their own mother.

Autumn Joi Knight often jokes that her name is a conceptual art piece attributed to her mother (who was not a cat). Her mother–also a Third Ward native–actually worked in HISD’s transportation department. “She was a supervisor of the bus route so she knew, basically, all of these schools in HISD,” among them, Longfellow Elementary School. A friend of her grandmother’s was kind enough to take her to and from Longfellow every day. There, she played violin, participated in the after school dance program, and in the theater shows. Later, she recited Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech to earn admission into the theatre program at Johnston Middle School (now aptly named Meyerland Performing & Visual Arts Middle School) and chose visual art as her second concentration. “I was always a kid who made drawings,” she recalls. “That’s really my first kind of art. Visual art, contemporary art, drawing, painting… all that.” Though she had developed a small portfolio, she opted instead to audition for HSPVA’s Theatre Department at the suggestion of her drama teacher. After all, she was always the kind of kid who liked to talk to herself in different voices–sometimes even creating different characters with different names. Knight says that although she grew up in a Black neighborhood with mostly Black friends, she knew excellence in Black art existed because she observed it in her Black peers at HSPVA.

“When I got to PVA, there were so many Black students and there were so many of them from Third Ward that it became this history of association. “

“Honestly, given the number of Black students in my class, it’s possible that there were some checks and balances put in place to ensure that Black students were better represented at HSPVA.”

Herman’s senior photo. Photos courtesy of Matthews.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

I later looked to Elaine Clifton Gore’s book, Talent Knows No Color: The History of an Arts Magnet School, to see if she addressed this phenomenon. When Principal Norma Lowder decided to retire in 1988, HISD charged her replacement, Principal Annette Watson, with increasing the school’s racial diversity–seemingly in response to the ever-looming pressure of federal district court orders. By the time Knight began her freshman year, the 70% white student population had fallen by 10% and the minority populations had trended upwards in proportion. This was due, in part, to Watson’s elimination of administrative interviews in the admissions process (Gore, 52-87).

It is unclear what effect, if any, Principal Watson’s reign had on racial diversity amongst faculty. However, it is clear–in talking with Autumn and with other 90s graduates–that the school’s Black educators (Ms. Smith-Williams, Ms. Pryce, Ms. Fiawoo, Mr. Boyce, Ms. Bonner, and Mr. Meloncon) knew how to bridge the gap and make their presence felt. “Even if you didn’t have them in a class, they very much all stood out in a very distinct [way]. “Ms. Bonner… she knew everybody. She knew every Black student,” including Mekeva McNeil (Theatre ‘96), a very close friend of Knight’s and a powerful force in Houston’s theatre community. In June 2021, when McNeil transitioned into the next realm and her loved ones gathered to celebrate her life, Knight was surprised to be recognized by Ms. Bonner and warmly greeted by name. What a blessing it is to have elders in our community who consistently see and hold space for us.

Thomas Meloncon was another impactful Black art area teacher at PVA. He wrote many of the school’s Black history plays, and Knight participated in almost all of them during her time there. “It was really important,” she reflects,

“it was where all the Black students got to kind of come out of the silos of their art forms and do this extra thing.”

At HSPVA graduation. Photo courtesy of the artist.

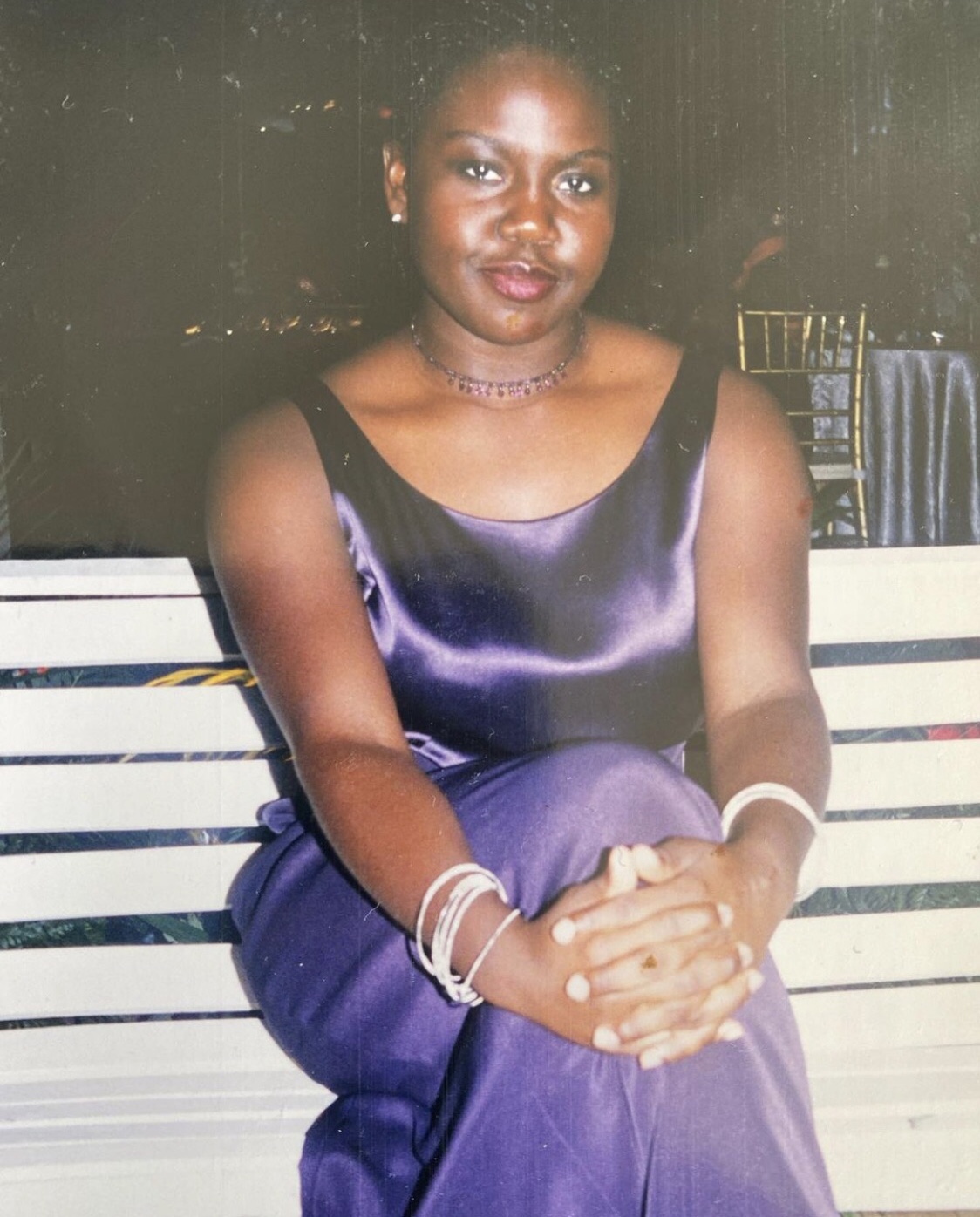

At Dillard University. Photo courtesy of the artist.

I later looked to Elaine Clifton Gore’s book, Talent Knows No Color: The History of an Arts Magnet School, to see if she addressed this phenomenon. When Principal Norma Lowder decided to retire in 1988, HISD charged her replacement, Principal Annette Watson, with increasing the school’s racial diversity–seemingly in response to the ever-looming pressure of federal district court orders. By the time Knight began her freshman year, the 70% white student population had fallen by 10% and the minority populations had trended upwards in proportion. This was due, in part, to Watson’s elimination of administrative interviews in the admissions process (Gore, 52-87).

It is unclear what effect, if any, Principal Watson’s reign had on racial diversity amongst faculty. However, it is clear–in talking with Autumn and with other 90s graduates–that the school’s Black educators (Ms. Smith-Williams, Ms. Pryce, Ms. Fiawoo, Mr. Boyce, Ms. Bonner, and Mr. Meloncon) knew how to bridge the gap and make their presence felt. “Even if you didn’t have them in a class, they very much all stood out in a very distinct [way]. “Ms. Bonner… she knew everybody. She knew every Black student,” including Mekeva McNeil (Theatre ‘96), a very close friend of Knight’s and a powerful force in Houston’s theatre community. In June 2021, when McNeil transitioned into the next realm and her loved ones gathered to celebrate her life, Knight was surprised to be recognized by Ms. Bonner and warmly greeted by name. What a blessing it is to have elders in our community who consistently see and hold space for us.

Thomas Meloncon was another impactful Black art area teacher at PVA. He wrote many of the school’s Black history plays, and Knight participated in almost all of them during her time there. “It was really important,” she reflects,

“it was where all the Black students got to kind of come out of the silos of their art forms and do this extra thing.”

I mentioned that for this year’s Black History show, Kinder HSPVA presented their second production of The Wiz, a classic film Knight has–coincidentally–referenced multiple times throughout her work. It shows up most prevalently in the last of three installments produced during her summer 2020 residency at The Kitchen in New York.

Assuming the role of The Wiz’s receptionist, she invites the livestream audience to call in with any requests they would like her to relay to her boss. While discussing the residency with curator Lumi Tan, Knight talks about being inspired by themes in The Wiz and says it got her thinking about “how institutions are created by those who assume authority over an institution,” in this case, The Kitchen.

At Dillard University, the HBCU Knight attended after high school, there was no question of who held the authority. “My professor there was like, ‘we doin’ Black plays by Black people with Black casts, directed by Black people, written by Black people.’ It was very ‘that’s what we do in here. Period.’” Though she recalls that PVA “had some moments here and there,” Knight explains that familiarity with contributions of Black art was something you simply had to seek out and learn for yourself. While discussing graduate school options with one of her professors at Dillard, Knight was encouraged to look into Performance Studies. This served as her introduction to performance art’s way of overlapping different art forms, something Knight’s background had certainly prepared her to take advantage of. “I felt like my mind just exploded,” she says. Some time after earning her B.A. in Theatre Arts/Speech Communications from Dillard, Knight enrolled in New York University’s graduate Drama Therapy program.

Knowledge of group psychology seems to have served her artistic purposes well. Viewers of her live performances will observe that, despite the inevitable attention-seeking efforts of certain audience members, Knight refuses to relinquish her authority as the group’s trusted bs-diffuser. Given the implied emotional labor that exists in those situations, I was curious to learn about any pre-performance preparation that occurs. “I prepare through my training and through my observation,” she says. “Before performances I really try to be alone by myself in the room to kind of really have a moment of quiet,” continuing,

“I can take care of myself by knowing that I didn’t let other people suffer from somebody wanting to kind of be disruptive.”

I wondered if Knight felt that her identity as a Black woman, well-versed in the act of codeswitching, made relating to and interacting with audiences an easier task. “Yes and no,” she begins. “I do think people respond a certain way to Black women or Black femmes doing a thing in public, so, to some degree, yes. In a very deep, social, psychological space, people are responding to the ways that Black women hold space and the way that they expect to interact with Black women, and there’s a multitude of relationships there.” She explains that those complex relationships are part of what make it “easier and more complicated at the same time.”

In the spirit of Women’s History Month, I asked Knight to shine a light on the Black femmes she admires. After listing several other artists and art-adjacents in her circle, I was somewhat surprised to hear who she named next: Whoopi Goldberg. “Obviously she’s got all kinds of things going on now, but Whoopi Goldberg was very, very important to me growing up.”

With Mekeva McNeil (Theatre ’96). Photo courtesy of the artist.

With Lisa E. Harris (Vocal ’98). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

She was drawn to the actress’s androgynous beauty, her command of herself, how she “held her own in all these different spaces,” and her humor which she describes as “very, very Black but also very personal, like ‘I am who I am.’” Considering that humor is heavily incorporated throughout Knight’s work, it was easy to make this connection. “Dynamic, EGOT, so dark skinned, playful, funny, can do all these different voices and characters, charismatic, smart… She was very important to me growing up.”

Knight also acknowledges the way growing up in Houston has informed her sense of identity and how she interacts with different groups of people. In addition to her round at Project Row Houses, various residencies in New York, and in other reputable art institutions this side of the pond, Knight has traveled internationally to take part in residencies in Panama, England, Japan, Jamaica, and Rome (as a recipient of the 2021-2022 Nancy B. Negley Rome Prize in Visual Arts). In thinking about her time at Project Row Houses and PVA, she notes,

“there’s just so much collective community. I think, when I go out in the world, I’m always trying to recreate that feeling.”

Somewhat impulsively, I decided to take a trip to Houston in an effort to familiarize myself with Third Ward’s dedication to community-building. In addition to spending time on Project Row and at Doshi House, I drove by what had named one of the “25 most dangerous intersections in America”: Sauer and McGowen Street. This was the place where Knight and Robert Pruitt’s experimental artist couple collective, MF Problem, held their public Sunday Social event in an effort to change the narrative from “most dangerous” to “nice place for a picnic.” My experience in these places did little to further my writing progress, but it did instigate various moments of introspection and allow me to better understand the connection between where we’re from and the selves we become as byproducts of our immediate surroundings.

Flyer for MF Problem’s Sunday Social. Photo found on Not That But This

Studio Museum performance of WALL. Photo by Paula Court.

Photos by Dorothée Brand/Belathee Photography © Akademie der Künste, Berlin